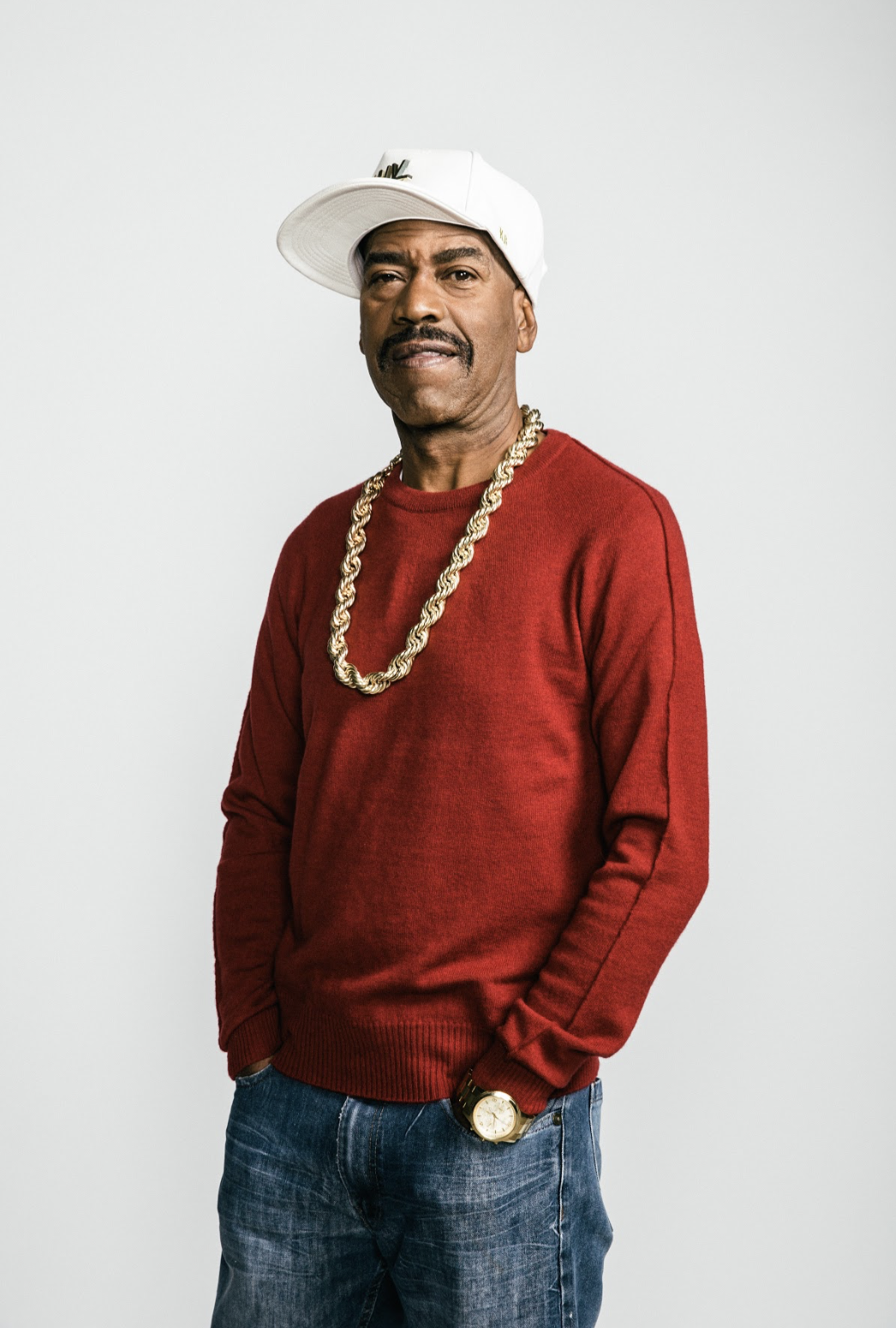

Open Mike Eagle

Photo credit: GL Askew II

LISTEN TO MICROPHONE CHECK: OPEN MIKE EAGLE ON SPOTIFY.

ALSO, FOLLOW US ON SPOTIFY!

We’ve been looking forward to sitting down with Open Mike Eagle because we knew he’d give it to us straight.

We’ve wanted to talk about what’s really going on in the lane he works in — known but not constantly recognized on the street, supporting himself and his family off music, but putting in crazy hours, and years, and miles to carve out that position, and at a place with technique and confidence where he’s now — especially with his new EP, What Happens When I Try to Relax, able to express what he’d had to hold in back in the day — but not sure if he’s reaching the audience he most wants to reach.

We talk here about structural things effecting a lot of people, like “investors” backing artists and white kids at rap shows, and the hypervisibility of black men.

And we also talk about just Mike’s opinions and experiences and hopes.

Get in there.

ALI: Welcome to Microphone Check, brother.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Well, yeah. Thanks for having me. This is a high honor.

ALI: For reals?

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Absolutely. Absolutely. Like I said, a fan of the show, fan of your work of course.

ALI: Thanks.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Yeah. It's good to be here.

FRANNIE: I think as – in hip-hop, and particularly your sort of status or the space that you occupy, where you're kind of – some people will recognize you. Some people will come up and talk to you. You really don't know what you're going to get.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: No idea. And I can't be surprised by anything.

FRANNIE: Right. And you aren't – your fans – somebody who looks like somebody who doesn't know anything about your work might be, like, your biggest fan – that type of thing. I don't think that's actually an experience that's particular to hip-hop musicians at your level of recognition at this point. It's actually kind of a weird thing that everybody's got, because of social media.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: I agree. I agree. I was listening to an interview with Pharoahe Monche last week, from Organized Konfusion, and while he was talking, I could hear – cause he was talking to, like, three people interviewing him at once on this podcast.

FRANNIE: That's rough.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: It was a lot. I've been meaning to tell them that, cause I know these people. I'm like, "Y'all have too many hosts."

But I was noticing how measured but excited he was to be answering these questions about his career and his work, and all I could think about in my head was like, "Wow. What it must feel like to take in this sort of exultation and edification in this moment." And then when he goes to the grocery store, I imagine most people there don't know who he is.

And like you say, it's not just relegated to hip-hop artists or any entertainers even for that matter. It's just, yeah, everybody kind of has their own sphere now. And it's amazing how gigantic people can be as an entity right now, and be completely unknown to other people. There's YouTubers who have millions of subscribers that I have no idea who they are. I hear their names. I don't know who they are. I could walk past them on the street and have no clue.

FRANNIE: Right. Yeah. And what you make can really change somebody's life, and you could also not even make that much money off of it.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: True.

FRANNIE: The value is all screwed up.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Yeah, I mean, I don't know if it's all screwed up though, cause value, in that sense, isn't how capitalism works. You know what I mean?

FRANNIE: Yeah, I think we're saying the same thing, but yes.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Yeah, yeah. I guess what I was responding was the idea that it's screwed up, cause I don't think it's screwed up.

FRANNIE: You think things are valued the way they – that capitalism wants them to be.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Yep.

FRANNIE: Right.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: I think it's how it's planned to be.

FRANNIE: Right.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: At the end of the day, unfortunately.

FRANNIE: Right. And then also there's this way that, as an entertainer, artist, performer, you have to sort of curate how you appear in the world or how – think about how people might perceive what you do or what you say or whatever. And people who aren't entertainers or anything like that now know what that is like, now are engaged with that, and are cool with everybody acting like that. But I do think it's – you're kind of aligned with the zeitgeist in the way that you're talking about kind of having one foot in and one foot out of celebrity, or notoriety.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Yeah, I think I occupy a really weird space. And I know that we just got through talking about how it's not that weird, cause everybody goes through it. But I think within hip-hop specifically – I've been thinking about it so much lately, how strange of a thing it is in this day and age to be, like, doing hip-hop with the force that you have to do it with to do it for a living, without any investors. Like, that's kind of crazy. That's kind of an insane thing to wake up and do every day.

FRANNIE: Yeah.

ALI: But wasn't it like that in the beginning?

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Yes. It was.

ALI: I'm just –

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Absolutely. But I think it's really different now though.

FRANNIE: What do you mean by the beginning?

ALI: Like, when there was two turntables and a microphone and a nice tape deck.

FRANNIE: OK. Yeah.

ALI: And you just pass it out to the people. No investors. You just expressing and having fun.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Yeah. And that's the thing. I think that people who I call my peer group, like the investor-less people who get out here and do it everyday, I think that's the spirit that we're carrying on, cause that's the way hip-hop was exposed to us. It's like, a thing – you can just pick up the microphone and do this. You don't need a microphone. You can do this while you walking to school. You can do this in the alley. You can do this anytime. The instrument is you. Go for it.

The business of it is such now though that you don't feel as validated by just being good at it, you know, or just loving it or whatever. Cause I came up in that love era where loving to do it meant so much, and to the point where there was even a section of the business for that, where if you loved it, that was – there was music made to appeal to you, and you felt like, "Oh, I can make that kind of music. I can get on that way." And that's disappeared now, in terms of the big money spectrum. Cause it seems like it's just big money now. It's either hand-to-hand or big money and then nothing in between. That's what it feels like.

ALI: Yeah, I wonder about that, from the perspective of: was there ever really support for the real stuff? From the business perspective. Or they just to happened invest in what was brand new and unfolding at the time, and there weren't many other alternatives to, I guess, distract from the purity. I think the purity of hip-hop was stronger at that point in time, so obviously the investors were focused on that. And now that there are other greater distractions that they can make their money on, and those distractions aren't really a force of change and goodness, it's different now.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: I'ma put my theory forward. Cause, like I said, I think about all this stuff a lot, right. And I think what it really comes down to was there was a time when, for me or you to anybody to really engage with music, popular music, manufactured music, you had to pay ten dollars per unit. That's just what it was. If it was CDs, tapes, records, whatever, it was at least ten – maybe it was $8.99. Round it up to ten. And what that meant was if I had my CD book with 300 CDs in it, that's $3000 I have spent to enjoy music, to have this collection, to show these are the things that I'm interested in. And in my case, there was a lot of that music that represented the love of hip-hop in that.

But when I really think back to when Napster happened, cause I remember. I was in college. I remember that semester when the homie who had a computer in his dorm room, and he had that dorm Internet, that T1, and he could actually download whole albums in like ten minutes, that's all we did. And for as much as we loved it, we was the first ones to stop paying for it, the first ones. Like, the people who still wanted the bigger acts, they still went to Coconuts and Sam Goody. We was sitting on the computer, looking through each other's folders and not paying for nothing.

So I feel like at the end of the day, when you the record company, and it goes from, "OK. We're making however many hundred million dollars a year on this industry, but suddenly this 20 million we was making off of this music with the love in it is gone," then why would they still put resources towards that?

I remember when – man, I think it was a De La album. It wasn't Stakes Is High. I think it was one of them first Bionix records that came – oh, AOI records. And I think it did 300,000, and everybody was like, "Oh, that's a flop." Which is crazy now, but the reason that it wasn't doing as – it wasn't like it was just super worse than anything. It was just we was fully in that era now of the downloading. And I think that when you look at it from that perspective, and the corporations, where they're only going to want to put money in something if there's a return, and we not putting no money in it anymore, and we stopped getting product.

FRANNIE: Yeah. I remember that time very well. I had forgotten about T1 though.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Cause we got T1 in our pockets now.

FRANNIE: Very important to my life at one point. But don't forget, we were actually paying like $17.99 at that point, and we were pissed.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: True. I was only paying ten, cause I couldn't – I maybe couldn't get it on Tuesday. I might've had to wait till the next week or whatever.

FRANNIE: OK. I mean, there was the – it didn't feel fair.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Right.

FRANNIE: And we knew – we were very clear that that money was not going to the musician. But there was also around that time – Jurassic 5 was kind of popping, right? And so that comes out of a world that you came out of, right? So I guess my question for that is: how does the audience play into this dynamic that you guys are talking about, this making a choice to vote with your dollar or whatever, but also this whiter mainstream audience that is going to spend more money? And when acts like Jurassic 5 – that's a mostly white audience, right?

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: I think everything is a mostly white audience.

FRANNIE: Yeah.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: And I think that's inescapable. I feel like when I was growing up that wasn't quite the case. I feel like I used to go to shows and see a lot more people that look like me in the audience, for acts that I would go see. But ever since I've been doing shows, which really started maybe in 2005 or '06, it's been mostly white people. And I don't – I can't – I wish I knew the reason why that was, but that just seems to be the reality.

I've never – like, me and my – I'll keep referring to this peer group, the cats I know that really do this and we're all kind of on our own and we kind of share best practices and all that, we're constantly trying to figure out like, how do we reach more black people? How do we do it? We can't seem to figure it out, how to get the message out to young people who are in the positions that we were in when we were young, when a Tribe or a De La or an MF DOOM or whatever it was that we saw that was like, "Oh!" And it cut through, and it was like, "That's what I resonate with, or what resonates with me." We don't know how to do that.

We don't know how to put it in a place – I mean, we put them in the places where everything else is, so I put my stuff on YouTube or put my stuff on Spotify, put my stuff everywhere I know to put it, but how do you get the marketing of it to reach other audiences, specific audiences. We don't really know how to do that.

FRANNIE: Was that something that you guys worried about, like Midnight Marauders-era?

ALI: No, we definitely played to majority of audiences where there were more majority of white people, but we used to scratch our head like, "Wow. How'd that happen?" But when we first began, it was playing small clubs in Manhattan that were black-oriented clubs. So once the music is broadcasted outside of our local areas, it broadcasts it into something that was more diverse, and so for us, it all was happening at the same time.

It was a quick shift, because we were kids doing demos in small clubs to all of sudden now things are more national. And once that happened, you find yourself in, like, Portland, and –

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Where do they hide the black people in Portland?!

ALI: Yeah, landscape is real different.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Man!

ALI: But you're just like, "Oh, OK. Maybe that's just in Portland." And then you go somewhere else and you're like –

FRANNIE: Wow. Yeah.

ALI: "OK. I guess our music is reaching more people than we realized at the time." But it's not a conscious thing. It's just something like once you at a show, and you're like, "Oh, OK. Wow." "Throw your hands up," and when you see a wave of a lighter skin, it's – it's – I don't know how to describe it. It's just, when you're on a stage and you see that, it's like, "Oh, shit."

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: I mean, the difficulty we're all faced with as creators is you sit in your lab, and you make what you want to make, and you really don't have anything in mind typically except what you think is dope.

ALI: Yeah, exactly.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: And you can never tell who it's going to resonate with. You just can't ever – I feel like the marketing people think about that, and they'll try to dress it up however they want to dress it up. But the music itself, if it's any kind of potent, it's just somebody's expression. And you can't control who's going to mess with it.

ALI: I kind of want to go just one half step back though, and this was just a really dumb wiseass remark in my brain, was like, "Well, if you really want to do that, you'd have change your beats and your music a little bit to" – and I know that's a horrible thing to say.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: You know it's interesting, cause I can say, I think in my position, like I said, cause I think about these things, I have to really evaluate my stuff like that all the time. I really do. I have to ask myself those questions. And I'm not, like, anti-trap music or whatever. Like, I'm anti-certain types of content. It's certain type of stuff I don't like to talk about. But production-wise, a lot of that stuff appeals to me.

My most recent song I just put out, I think you'd call it a trap beat. It's got the same drum patterns and the hi-hats and all that. There's a little more of a chord progression in the beat – in the melody behind it, cause that's what gravitates to me. But is that what you mean, the style of beat?

ALI: Well, that was just one part of it definitely. Cause I was just sitting here thinking about your music, my music, other people's music who I consider peers in that kind of sound space. And there was a point in time in hip-hop where that spoke more to black people. But it just seems like life has evolved, and so the taste of what the younger blacks may be into – not saying that they don't appreciate music like yours or mine, but it's just, it's a different frequency, a different language, at this point.

So when you say you guys are trying to figure how can we get this channel more towards black people, I'm like, "Uh." I don't want to use the word dumb it down, cause that's again – that's a horrible thing to say, but it's just make these different choices I think, if that's really a question you want answered.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: I want to go with you there, but then Kendrick will put out something that's just the weirdest, blackest, funkiest shit ever. You know what I mean? It don't seem to fall in line with everything else.

ALI: True.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: It seems more like – although the production value is way higher than my stuff, I feel like it comes from the same –

ALI: Same place.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: – place.

ALI: Yeah definitely.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: And so it makes me feel like, "Damn. Maybe you don't have to dumb it down."

ALI: Well, OK. Let's not use the word dumb it down, cause that's just not the idea I'm trying to put out there. But – and I'm not saying that you need to do this, but just when you bring that up, and the thing that Kendrick does though is he laces the really unique and different and what we call weird or strange music with something that's just so simple, straightforward. It's like, "Oh, I got that in my mouth. I know what that is. Oh, you just gave me this other shot in that drink, and I'm open to it now, where I might not have been." And so –

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Got you. So it sounds like you're saying accessibility.

ALI: It may be a factor, no different than jazz. With jazz music – I love jazz, and I don't think that it should be altered specifically just to speak to one or any specific group of people. I think it should just be what it is. The music is what it is, whatever you feel it to be. But one of the known complaints is a lot of black people are not into jazz and that's a sad thing, considering it's black people's music, no different than hip-hop. And you go to see jazz musicians perform, and there's a lot – there're not so many blacks supporting that.

So then it's like, OK, so what do they do in jazz music to get the people in. Well, make some jazz trap. I don't know. That sounds –

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: It does exist.

ALI: It does? I was about to say that sounds ridiculous, but I didn't know it existed.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Yeah.

ALI: I need to broaden my horizons. But I think when you just do what you do, and it has the purity of your intentions in it, then whoever's supposed to get it is supposed to get it.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Yeah. And that's typically where I'm coming from is that. When I'm in my rawest creator space, those are the thoughts that occupy my head. Like, let me just execute this vision and worry about all that later. But I do end up worrying about it later. You know what I mean?

Especially now, business-wise, I'm stepping out on my own. It's my first time not on a label, putting out my music myself. So more than ever, I'm thinking about those things as – cause now I'm the one investing in the PR budget, investing in the videos, investing in the artwork and layout and all of that. So I have to – I feel like I need to have a little bit better of a gauge of how it's going to do versus the money I'm putting in.

ALI: So you're conscious of that, so when – is it titled Relatable?

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: The single is "Relatable."

ALI: The single.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: The EP is called What Happens When I Try To Relax.

ALI: Interesting title.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: I'm good for those.

ALI: No doubt. So are you thinking specifically about how, no pun, how relatable it's going to be to people when you're making a song like that?

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Well, the thing is that's part of what I was thinking about when I was making that song – the song is real complicated. And that's ultimately the – not the issue, but that's the circumstances of my music, is typically if I'm writing a song, it's not just for one reason. Sometimes I dial in on something super one subject, and just write on that. But typically I'm thinking about different things.

So with that song in particular, I'm thinking about relatability, but I'm thinking about it in terms of engaging in small talk with people and relatability as a concept when I'm feeling super weird. But if I'm in a small talk situation, I can't necessarily embody that. I have to think about ways in which I feel like we can have a common ground with people, even if I don't really even believe that. And that's kind of where that song was coming from. So when I say I'm relatable in that song, it's almost like I'm trying to tell myself I'm relatable. And that kind of fluctuation of emotions and that self-talk, all of that is in the song.

And so ultimately it leaves with a product that is difficult to explain, which is not something that usually sells well. All that stuff is stuff that I do end up having to think about after the fact, and not have to necessarily, but I feel like it's in my best interest to, to have a handle on that kind of thing.

ALI: I don't want to beat a dead horse on this, but where was your head when you were actually writing it and attacking it, cause I hear – as you're explaining – the reason why I ask that is because, in terms of your flow, that was reminiscent, just the cadence of it was reminiscent of some of your other works, but it was something in the energy of that song that I was like, "Oh." I had a, "Oh shit. This is it."

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: I'll tell you the story of that song. I – man, I was with my kid one day, and I don't even remember what was – I feel like I was putting him in his carseat or something, and I don't know why, but for some reason I started thinking about trying to explain to somebody that I was relating to them. And I don't know where it came from, but that just popped into my head.

So that was just something that was rattling around in there, and then I got to hearing beats for the new project, and as this beat came on, that kind of phrasing, "I'm so relatable. I'm hella relatable." And then the way that cadence was, "duh dah duhduh dah duhduh, duh dah duhduh – OK, that's interesting."

And then when I started writing, I started feeling that self-talk thing kind of happen, and it started infuse it with a little bit of emotion, and I made sure – I probably recorded that song like seven or eight times, just to make sure it felt how it needed to feel. And that's – I think that's just a phase I'm in now as an MC, as a recording artist I should say. Cause I put out my first album in 2010, and when I listen back to it now, I'm like, "Damn. I could write. I didn't know how to record at all."

So what I did with that energy was I kind of married the writing and the intention to an energy that I kind of have when I'm on stage, that live energy where I'm trying to express emotions to the room. And I wanted to make sure that that was in there.

ALI: It was a lot in that song, and it made me go, "Oh, this is different."

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Word.

ALI: And there's similarities to some of your previous works, but there was something in the energy of that, I was like, "This is it." That comes with time. That comes with living. Sometimes it's an awareness that you are – when you're going in to record a project, you're like, "I know what my job is. I know what my responsibilities are here." And sometimes it's just accidental. But it sounded real – it sounded refined and deliberate.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Well, that's good, cause I worked on it a lot.

ALI: Not saying that your other music doesn't sound deliberate. It actually sounds like you put a lot of time and thought into your music.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: I do, but I think there is something to be said about experience recording, and how that can give you a more refined technique.

FRANNIE: Yeah, and I mean, part of it is that that song, the feeling that you have as a listener, you're not – you're a little bit uncomfortable.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Mhmm.

FRANNIE: And that's the kind of thing that makes it hard to build – get easy fans off of, right?

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: True. And it's another wrinkle in this song, and as we're talking about it I realize that's the part that's kind of unsaid, is that I picked that cadence over that kind of a beat as a means of distilling certain elements. People like this tempo right now. People like these triplet flows right now. I can do that, but let me do it how I would do it. And so you cancel out those parts, and you get this real healthy dose of me and my aesthetic, and that's definitely in there too.

FRANNIE: But then also what's in that song is – another thing that's maybe unsaid so far is that what we were talking about earlier, these feelings of kind of being on display a lot or having to control yourself, the hypervisibility and double-consciousness is particular to black men in America and other oppressed people in other societies, situations.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Absolutely.

FRANNIE: So I mean, kind of going back to this idea of audience, you know, as a performer, and especially – and I want to get to this other song, my actually favorite song off the EP, "South Side '93 Bulls," right? That you're trying to reach the black kids at the white shows?

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: "Trying to reach black kids in a room full of whites."

FRANNIE: "Trying to reach black kids in a room full of whites." So that's like the opposite of what you're talking about before, just being surprised by the white people trying to reach the black kids. How much is that is a choice that you want to make as somebody who's a little bit older, has more experience and more experiencing traveling the world? And how much of it is something that you don't really want to deal with or don't think that needs to be dealt with by you specifically when you're younger? I mean, is it something that you kind of are just like, "Well, I have to?" Or is it something that you say, "Now I want to?"

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Are you talking about reaching black kids specifically? Is that –

FRANNIE: As an overt – as a lyric, as a thing you're going to have to do on stage.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: I guess I've made similar statements to that before, and it is a challenge sometimes on stage. It is – I'll have a moment sometimes where I've committed to performing a song, and I'll get a couple bars in front of that bar, and I'm like, "Yup, I'm about to say this shit in front of all these people. Again." And it's something to deal with, but I feel like – I don't say every controversial thought I have, but I feel like that's an important one.

And I feel like it is because of the macro perspective of black plight. And I don't necessarily feel like I have a lot of power, but I do feel like a way I can help is to show young black people that there are other ways to do things, just to be – not a role model in a sense of, "Do things like me," but a role model in a sense of, "I am a fully functioning adult, and I handled things way, so this is a way that things can be handled."

And so – cause I feel like that sort of symbolism, of there being choices, was important for me growing up.

FRANNIE: Yeah. The representation of options.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Yeah, exactly. And it's important for me, and it's always felt important for me. There's lyrics on my very first album about that.

I've always worked with kids too. When I had day jobs, they were always working with kids, and I would always pay a lot of attention to what are young black kids into. What are they seeing? What are they patterning themselves after in terms of media representation? And I feel like that lack of alternatives is kind of stark. And a lot of that was before Kendrick came along too, so it felt really bad.

FRANNIE: So as much as you've been doing this for as long as you have, the availability of rappers, black male rappers, being vulnerable, in a whole bunch of different ways and also just being – having their humanity just out there, and selling a shitload of records, that's a very – a fairly recent development.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Yeah. It's very different now.

FRANNIE: So why is that happening now, and what was preventing it from happening before?

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Could you give me an example of what you think is a good display of that, this happening now?

FRANNIE: Drake.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: OK. But now, his vulnerability is –

FRANNIE: Performative.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: In a sense.

FRANNIE: I see where you're going with that.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: In a sense. And that's not to take anything away from it, cause it is – it's better to have that than to not have that. But I'm a little cynical –

FRANNIE: Same.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: – so I tend to look at that like, oh, that's great that that's happening, but it feels like, I mean, maybe a marketing decision? An angle. It feels like an angle.

FRANNIE: Yeah. I mean, "Nice For What," is he just read the room and gave that out.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: It's pandering. Yeah.

FRANNIE: Totally.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: And it's great. My wife loves that song.

FRANNIE: I needed it very badly. Yes.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: I'm like, "Awesome!" But when I hear it, it feels like a commercial to me.

FRANNIE: So who's a better example?

ALI: That's what I've been sitting here trying to think. I'm like – I'm going through the past ten years like, "OK. There's – who? Someone."

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Huh. Well, this is a thing, right? If you look at a guy like Joe Budden, when Joe Budden was fully fully rapping, he had some of the most vulnerable shit in the world.

FRANNIE: That's a good point.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: He had eight minute songs telling all of his business.

FRANNIE: Yeah.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: But yeah that never really became, like, a big thing.

FRANNIE: I mean, Wayne will talk about depression.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: He will. Wayne changed the game in a lot of ways. I think a lot of the expression that's allowed right now is because of him.

FRANNIE: Yeah.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Yeah, cause during the gangster-est of the gangster-est time in rap history, he came out and said he was a Martian.

FRANNIE: Right. And played the guitar.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: And everybody was like, "Alright! Alright. We can be Martians now." Skateboarding and all of that. I feel like his willingness to indulge in his own relative weird tendencies for the time really opened things up. I think that opened things up a lot. He seems to be very vulnerable all the time. But I'm still having a block too, thinking about –

FRANNIE: I'm trying to think about the chart right now, and I can't even picture it. I guess what I'm most interested in is this idea that it used to be impossible or hard to find.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Kanye's vulnerable. Now Kanye – what's going on right now I can't even fathom honestly, so last three months aside –

FRANNIE: Kanye's, like, actually vulnerable. I don't know that he's giving you a vulnerable song.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: I think he has though. I think –

FRANNIE: Oh sure, in the past.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: In the past, yeah.

FRANNIE: No doubt.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: I think he might be the forerunner in terms of saying uncomfortable truths about himself on records.

FRANNIE: For sure.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: In ways that didn't seem pandering, but just seemed somewhat powerful, and maybe – I mean, maybe he went too far in that. Who knows?

ALI: It's interesting, cause I actually was thinking, do I ask you about Kanye, or do I leave it alone? Because I see similarities in terms of your truths and your speaking them and being unapologetic to, "This is the way you feeling about things." And others may agree with some of the content. There's things that you put out there that's information people need to have. And sometimes I think what I get from it is your presenting as, "This just how I feel." Like, "There's my filter. No one else. Doesn't get in, doesn't get out. That's it."

And listening your music, I felt like, "Hm, maybe something in the water in Chicago or something." But you guys just have that very unapologetic, very in tune with self and feelers, and just saying how you feel.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: I come from literally the same part of town as Kanye, the South Side, and I was steeped in the rap culture – the specific that birthed me, I'm talking about like '96, south side of Chicago. He was already in that, making records and producing in Chicago. So he was the name I used to hear about sometimes.

Cause I used to run into Rhymefest all the time. I'd be cyphering with Rhymefest. He's the first person I ever heard freestyle in my life, and I was like, "OK." He was the one that made it accessible for me. Like, "I'm going to freestyle now," cause I heard him freestyle.

But that environment was very specific, and we were all surrounded by crazy gang-banging, kind of like here in L.A., but a little different. And hip-hop for us was a uniform that really legit saved our lives. There was red and blue and all that going on in Chi, but it was GDs and Folks and Moes and Black Stones. It was a giant war going on, but I could rock a bright blue jacket, have crazy hair, and ski goggles and baggy pants and shell toes or whatever Adidas I could afford at the time, and be able to walk freely, because they knew I wasn't on that, based on my uniform.

And I feel like maybe what you talking about in terms of that kind of – the force of that personal truth, I think that's maybe where it comes from. We had to rap ourselves into our existence in a way. And that's also – we validated each other when we did that, and cyphers – the punchlines that hid the hardest were the ones that were just the most affirming. So I feel like maybe that's where that comes from.

FRANNIE: Yeah, "South Side '93 Bulls" is my jam.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Word. Thank you.

FRANNIE: There are a lot of moments on that song that I thought just really needed to be said, and I've heard musicians say privately or off mic or whatever, but not on an actual record.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: It's my first time talking to any other human being about that song. So this is an interesting moment for me.

FRANNIE: Cool. Well, making an audio mirror you can walk through is – I don't know. I never thought about a song like that, that that's what it really is, if you're doing a specific thing. And man, I feel a lot of pressure right now, and I feel like my question is not that deep. But I'm going to go in there anyway.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: That's OK! Maybe that's good. Maybe that's good. Maybe I'll end up talking about this song a lot, and you'll ease me into it. That's cool.

FRANNIE: OK.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: That's super chill.

FRANNIE: But I was thinking about all these podcasts that you've been on, and you had a podcast, all of that shit. But all the – but then earlier what I was thinking about how do you get more black fans, and we didn't talk about this other sort of part of the infrastructure, which is the press and what gets pushed and the lenses through which it gets pushed, that type of thing. And how – I think journalism is failing musicians right now.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: That's a really interesting perspective.

FRANNIE: You're – a bar in it is, "If you're going to write about me, get it airtight," which I think is just the lowest possible expectation from a musician to that world. And I just don't understand the financial reasons that things are as bad as they are.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Clickbait in journalism.

FRANNIE: Yeah, but it's not even that much money, and there is more money to be made –

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: But it's some money.

FRANNIE: What? It's some?

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: I feel like – cause specifically the instance that I was referring to in that song was about a website that wrote this article, and it was crazy to me, cause it was about how all these rappers that are quote unquote underground are – how they're mainstream now, because the game is different or whatever. And I engaged with them about this piece, in affirming that I'm not mainstream. I'm very much – cause they were almost saying the underground doesn't exist anymore or something like that. And I refuted that and pointed at myself as an example, and they refuted me saying, "No. You're mainstream."

And I'm like, "No. That's" – not only is that not true. I felt like it was dangerous. I felt like – it's already a problem for me and my peer group that when our records come out, if anybody who knows who we are, they're going to talk about our records with whatever other rap came out that week, whether those rappers have investors or not. And that's – it's a crazy disservice, it feels like, to us sometimes how you put them in the same sentence, but we don't have no resources. We're making music with nothing to survive. Meanwhile there's people who – they can afford to make 300 songs and pick the best 15.

And so in that, I feel like the true understanding of where we are and where we come from is understanding that we don't have anything. So don't call me mainstream. That's crazy. If by some weird fortune that were to become true, I would certainly live in that. But I think that's really unfair thing to say to me and the people who I know who have to work how we have to work, how – we have to do crazy things! We have to get on airplanes to go far away places, and you don't know – you see ticket sale numbers, but you don't know what it's going to be like.

We don't have hit records, and that's not because we don't like hit records. We just don't really have access to that sort of machinery. And I'm not saying that like, if we did, then this would be the mainstream music. But we just can't even afford to think that way. And so to me, it necessitates having a distinction until that reality changes somehow. And it was the real beef with that website for a minute. I think it's since resolved, but that's where that came from.

But anyway, I said all that to say, the reason that they did that article was they wanted clickbait headline, you know?

FRANNIE: Yeah, I know.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: It made more sense for them financially to have an argument that looked crazy, cause people would click on it. Cause that, in that sense, would make them more money than writing a really great article about some people that people don't really know about.

FRANNIE: Yeah. I'll just say, with my experience in that world, that's not always the case. What really actually makes you money, mid- and long-term, is quality. Like, it's just a fact. People want to read. People want to learn things. Just publishing the same shit that everybody publishes isn't a good business model. So I think there's other motives there. But that's just me.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: I would be interested to hear them.

ALI: Well, I'll give a theory. I think that journalism does not escape any of the characteristics of capitalism than any other institution really, and so it's – certain things are going to sell, is going to captivate, and even though it's – you're in the position of being a truth teller, but what's the truth? These days, in perfect example, is just the word alternative facts, and the mind state of that and what that really says about our willingness as human beings to be deceived and duped and to go along with it and be like, "OK. That's cool." And it becomes a bit of normalcy normalcy.

FRANNIE: It's received wisdom that clickbait makes you money. It's not true. I mean, but I think what we're talking about is this – there's rap. There's the whole rap vs. hip-hop debate that I don't want to fucking have. There's the art rap thing. There's independent, right?

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Yeah, that's – I think that's where the meat is these days, is that term independent.

FRANNIE: Yeah, that's where all that shit's happening.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Cause that's a damn near insidious term now.

FRANNIE: I really like this idea of investors rather than deals or labels, cause that's really – that's what's actually happening.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Right. And that's the thing. If you have just as much resources that you didn't have to necessarily have on your – resources from other entities, if it's straight from the distributors or if it's from Apple or if it's from –

FRANNIE: Ooh, I thought that's where we were going.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: If you have that much, if you have that many resources, is it still independent just because those resources aren't coming from a record label?

FRANNIE: I don't think so.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: I don't either. And I feel like that –

FRANNIE: Because you have to pay people back!

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Right.

FRANNIE: Because you have to make money to pay people back. That's why it's not different. Even if it's your dad. He's like, "Going to need that back at some point." And then there're all these things that perpetuate that or that support it that we don't talk about in those terms, like micro-genres or – just all these things that are incompatible that influence the ways that music is written about, read about, shared, consumed, all that kind of stuff.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Marketed.

FRANNIE: Yeah, I mean, we just end up talking about things that aren't actually real.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Yeah, narratives. You end up talking about narratives. But honestly, that's what any product really – you end up talking about narratives, and –

FRANNIE: Yeah, but I feel like it's a crime in this situation.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: I understand. Cause it's supposed to be something different. It's supposed to have more substance, and it's supposed to be based on the quality of the work and some natural human emotion that it evokes. But even if you look at visual art –

FRANNIE: Yeah. Totally.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: – the shit that sells has got a narrative.

FRANNIE: Totally.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: And that's – I'm not afraid of that personally, but what I don't like is to see – there's particular fake narratives I don't like. There's particular fake narratives that really bother me. Like, the overnight sensation narrative bothers the shit out of me. Cause I think that's not just a lie; I think that's a destructive lie. Cause that's not – it's impossible! There's always some planning involved. There's always some structure and execution involved.

And I find myself having to tell all the super talented broke rappers I know that that's how it goes, that they're not just going to sit on their couch and be dope and things are going to happen for them. Cause that's what that narrative makes them believe, that they're going to get discovered. And it's just not what happens. You have to know how to answer an email. You gotta know how to show up on time. And that's just the basics. And then you gotta know how finish a project, and you gotta know how to shop it, and – there's all of this stuff that – it's not included in these narratives.

And it gets wildly disappointing to me, because I feel like if people had real access to real information, I think the landscape would be completely different. And I feel like it benefits some people to put out the bullshit so they can continue to do the kabuki stuff. I don't know. I think – there's just a lot of context that's missing from things, and it ends up upsetting me, cause I can see it.

FRANNIE: Same. Yeah, sobriety is another one that bothers me. So many people who are super successful are completely sober and don't talk about it. And the cost of that being absent from the conversation makes me crazy sometimes.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: That's really interesting.

FRANNIE: As a non-sober person, I say these things. But yeah, I mean, I'm going to calm down now.

ALI: That's a challenging one though. I'll just say that as a sober person, because people look at you and be like, "Of course, you would think that." You know?

FRANNIE: Right.

ALI: It's like, "Yeah, exactly." It's a fact, I think. I could be wrong, cause I haven't jumped to the other side. But I think it has a lot to do with I'll say my success in life, not talking about musical successes, just the way I am able to move through the Earth.

FRANNIE: Right. Well, then there's the other part that people don't talk about personal development. If you want to achieve your dreams, you have to do a lot of work on yourself, almost all of us did not come out the gate with any of these tools, and the idea that you can – it'll be fine, you can just not talk about it, not do that work, that's a lie.

ALI: I think you're right. I also think though the better example is not the one who's sober, especially someone like me who's never been – I don't know what the other side of that is – but actually someone who's been there and has overcome that to then discover, you know, what changed my life when I decided to stop doing something.

FRANNIE: You mean everybody's gotta learn it for themselves type thing.

ALI: It's not that everyone has to learn it for themselves, but it's the – I think the better representative is someone's been there, who understands.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Right. Rather than somebody who's never –

FRANNIE: I see. Yeah, sucks when people have to put their trauma on display for – to help other people though.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: And talk about something that's not talked about enough, trauma for sure, specifically the traumas that go along with what it seems to be a new – a celebrity in the modern age. It seems like it's harsh on people. I don't know if it's harsher than it ever was before, but we're watching people crack up now, like Kanye situation, whispers about Nicki. And who knows, cause we're so far away from it. But you see people do things that very much appear to be public breakdowns, and how do we help? What can be done?

Is there something about modern celebrity that's inherently harmful? I feel like those are conversations that need to be had, cause people are aspiring to be at this place, and it doesn't seem to be much there in the way of support. Because then everybody wants something from you, and you have all this pressure, and what do you do once you get there?

FRANNIE: Right. Does it look different to you from how it felt when you guys were just mobbed?

ALI: The dysfunctions are the same. The way we're able to view it is different. And so you had the – at least the moments of privacy that was a factor, a huge factor, to keep Humpty Dumpty. Now that veil is removed. It existed. We just were on the outsides, and that's due to technology and just life and evolution of environment.

So the dysfunction is the same. You can put in a year, 1972 to 2012 to where we are now, 2018. Those characteristics and behaviors of someone who's in – who's hurting, who's in a state of trauma, it's the same. It's just society has such an inside scope into someone's private life and a say, and what you say and think and feel actually now is adding to the trouble that you're dealing with. And now –

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: So it's multiplying.

ALI: – there's no filters! At least you had the filters of you can go, and your people can try and sit and talk with you. Now you're – you have the entire world now just chiming in on everything else that you thinking and feeling, which then you're reacting and responding to that. And I think that's maybe something we as society as a whole have to look at, ourselves and how we interact with one another now.

Cause you were asking that question a moment ago, and I was just sitting here thinking, well, we all decided either to take the red pill or the blue pill. Like, when you're talking about journalism and all these things, I'm like, everything is fake, if you really want to look at it, and we're drawing the line at what we decide we'll be the truth, our truth. And so what I mean by that is what if we all simply put our phones down just for a day. How much more truthful are we living our own lives, who we are inside versus all these other things that become part of our lifestyle that we addressing and dealing with?

So I don't know. You touched upon something that's just – it's so severe, so major.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: I feel like everybody put their phones down for a day, we'd have a national day of withdrawal.

FRANNIE: Yeah.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: You know what I mean? People would be freaking out.

FRANNIE: Just like headaches everywhere.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Yeah. Everybody would be itching.

ALI: And it's just not only that. I mean, if it was – let's just say, for example – and people would really protest on this – but if the government just decide, "Yo, for a week, we turn the electricity off, everywhere, globally, for a week. We're going to do that once a year. Whole week."

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: I was in Uganda in 2012 working with some youth out there on some rap stuff. In Kampala, Uganda, they make – well, in Uganda, they make more money selling the electricity they generate to neighboring countries, than they do having the people who live there pay their electric bill. So they do these rolling blackouts. And it was very different. It was very different. It was –

ALI: In what way? Like, for an example.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Cause we are used to a society where if you pay a bill for something, you expect it work until you don't pay the bill anymore, and if don't – if it stop working before that, you raise all kind of hell. You writing all kind of letters. You marching into people's offices like, "What's going on?" They deal with that there. They deal with these occurrences, and there's no information. There's no announcement. It could be a day. It could be a week, and they just don't know. And they just live with it. They just got candles on deck. They got generators on deck.

ALI: If you have a generator, you cheating. Nah, I'm just joking.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Well, everybody don't have a generator either. A lot of places I was at, they still – they use well water. Everybody didn't have a lot.

ALI: That's interesting. Did you feel a sense of more communal –

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Yeah. There was inherently more of a sense of community. You know what really tripped me out being out there? I've been in hoods all my life, all my life, hoods in all kind of different cities. I know what a hood feels like. I know what it is when I'm in the black people part of town.

And I was in Kampala, Uganda, and every part of it is full of black people, but one thing I'm used to seeing in the hood that I did not see in Kampala, Uganda, I didn't see no winos. I didn't see no crackheads. I didn't see anybody who had gone that far down any one of those roads to where they were no longer part of the community, where they were living on the street. You didn't see none of that. That's what jumped out to me. And I feel like that's gotta be a function of community somehow. Cause it's liquor there, just nobody's choosing liquor to the point where they can't function no more.

And I think part of that's got to be this feeling of feeling like you owe people around you to keep it together in some sense, depending on each other like that and from a very early age. You'd see kids, a group of kids, 3, 4, 5 years old, all walking to school together, no parents. They just really depend on each other a lot more.

ALI: Wow.

FRANNIE: I think I've heard you talk about hearing rap music outside of the U.S., what people pick up on, what it means for their conception of black American life. I mean, I wondered if you could talk about that, the idea of hip-hop as an export, but then also what it feels like when you're there, that it's an import.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: I was real sad the night we was in Kampala and we had – the guys that we were working with were people in the village that rapped, and they were both – they speak a language called Luganda, and so what we call rapping, they call Luga Flow. And all of that was dope, and I didn't know what everybody was saying, but I could feel the energy of it.

One night, they took us to an open mic spot out there, and it was tragic. What you saw was people impersonating the worst of what we export, the worst of it, just – Africans with long white tees saying n**** and saying b****. I'm like, "What? I'm in Africa, and cats is saying n*****? Does nobody realize how ridiculous that is here, of all places?"

But they don't – I think part of what it is out there too is that it's not like there's that much of an older generation that grew up with rap, to fill in the gaps. It's like it just kind of suddenly happened out there, and we were already in the middle of this black American journey, and they're just catching this image of it, that looks so opulent and looks so successful. And they're just embodying that, and there's nobody there to break down like, "No. There's so much trauma behind all of this." They don't get that unpacked for them, so they're just mimicking the image.

ALI: That's horrible.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Yeah, it was real bad. And then like I said, it wasn't all the rappers, but when we went to the rap club, it was like, "Oh, this is awful."

ALI: What did you leave behind?

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: We made a record. Me and this producer Ras-G from out here, we made an EP. We left a ton of music behind, and we tried to do a lot of teaching. We tried to unpack a lot of those things. We tried to explain the meanings of why things are done the way they're done. Who knows how much of that actually stuck, but that's what we tried to do, was just leave behind some knowledge and history and context.

ALI: In hearing that story, when I think about some of the younger rappers now and trying to educate them and convey to them that, yeah, you have success, but do you understand the backs you're standing on, and what you actually represent and why it's important that you look back? And unfortunately as some young people do, egotistically and ignorantly, they respond with ignorance.

But hearing something like that, I wonder how affected they would be, if they were in there to see a place that should not be the way of expression, if that would change some people's perspectives who are successful here.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: I mean, one would think, but there's just such a natural inclination for young generations to just buck everything that came before. That's just such the spirit of it, and eventually some survive and get wise and complete the circle. But this makes me think about the rock 'n' roll generation, and it was, "Fuck you, Dad!" All of that. That's part of it too.

FRANNIE: What about in Europe? Cause you're going to go to Europe soon, right? And you've talked a lot about how Europe is just different. There's a very different understanding, as an audience, of what they should do, how they should act.

ALI: Yeah, they still are clinging to I think the impressionism of America as really affecting the musical art form globally, and not always the best influence, just similarly to what you were speaking about. And so – but they are clinging by a thread to, I think, their way of really receiving art and contemplating art a little bit more deeply, not just taking it for what's on the surface but really trying to get to the underneath aspects of an artist and what they're saying and what they're trying to express.

And it comes across I think in some of the Parisian rappers, rappers from Germany, rappers from London, that there is a little bit of the fun and entertainment and sensationalism part of being a rapper, a storyteller, but then they also try to really keep the real connection to something that's real and grounded and not fictional. But I don't know. It's kind of changing.

FRANNIE: Has that been your experience?

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: I'm seeing the change. When I first started hearing about people going to Europe, I felt like they were telling me that it was more about the purity out there, and I think over the course of time I've been going there, I watched that change. And I think of course it's cause the Internet and accessibility. I feel like more and more Europe is hip to whatever – they're hip to and valuing whatever American audiences are at almost the same time, increasingly anyway.

I've had ups and downs and there. It started bad and gotten better. Just cause my career is really about going places and having a show, and the next time the show's better. That's really kind of the story of my career. But I face some challenges out there because when I'm out there, it becomes very apparent to me that my music is very American.

FRANNIE: I see that.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Yeah. The things I'm talking about, a lot of it is rooted in American life and understanding the dimensions of how things are out here and exploring that. So you gotta be hip to be able to really feel it if you don't live here. So although it's good out there, that is something that I face out there as an obstacle. My music isn't necessarily universal like that. It's very rarely just, like, an emotion that's transcendent that way.

FRANNIE: I want to proffer a theory about –

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Ooh, I like theories.

FRANNIE: – why there's so many white kids at your shows, and this is, like, a historical thing. And it goes back to what you were saying about realizing that – or just acknowledging that things are fake. I think that white kids don't know that things are fake. I think that when they find out that things are fake through hip-hop, it's really shocking, and kind of intoxicating for them. They want to know more. They're so engaged with this idea. They want to hear all the different iterations of it being fake, and hip-hop has just been that window.

And in a way, it's educational. It's a step. There's just an inherent difference that white kids that have no idea that it's fake grow up, and it takes decades for them to see things for what they really are, and partly cause understanding that is going to cost them some little tiny things along the way.

It's kind of baffling to me that it's still baffling to all of us, the attraction or the appeal or the –

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: It's more nuanced now too, because more than ever there are a shit ton of white rappers for white people to listen to too.

FRANNIE: Yup.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: It's blurred a little bit. I think in a sense, it's a little bit about access to resources too, a little bit about that. It's a little bit about knowing that there are things out there to search for. And I don't know what gives somebody that sense and doesn't give somebody else that sense. But the people who find me are people who know that there's something to be found.

And my experiences with my people, with black people, has always been that we haven't been as apt to search and seek out. We've been more apt to receive. We've been more apt to turn on the radio to whatever stations are marketed to us and listen to that. If I don't like this song, go to the other one that's marketed to us, listen to that. Less of a sense that there's an entire world to explore and everything in it belongs to them. And I feel like that, some percentage of that, is part of it too.

But who knows? I gotta start doing research. I gotta give a very detailed survey at the end of every rap show.

FRANNIE: I feel like that's going to do numbers. a) it's clickbait b) it's quality.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Yeah, it's both sides of the brain. It's perfect. Clickbait quality.

FRANNIE: Yeah, thanks for going into that stuff on your time with us.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Yeah! I think about this stuff constantly. It's good to actually have a place to let some of that out. You know?

FRANNIE: Yeah, yeah.

ALI: You're really highlighting the brilliance and excellence of black kids in projects or the ghetto neighborhoods that get overlooked. I feel kind of silly asking – I mean, it's kind of obvious – why do you feel it's important to express that? But –

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Just precisely because of what you said, cause it's overlooked. It's not part of the story. It's not part of the story. There's people of all kinds in the hood. It's just only one kind of story gets told. And ultimately if you look at even something as way out, extreme, and as happening often, unfortunately, as police killing black people, when you dig into how the officer described the person and the kind of words they used, it's all stuff where you can tell they think – they just think all black people are the same. They just – their association is one vile image, and there's no room for anything else.

And in that, I always feel like it's so important to explain to people, to demonstrate for people, that people in the hood are not monolithic. It's all kinds of people. There's extroverts, introverts. There's nerds. There's poets. It's basketball players. It's rappers. It's dancers. It's sculptors. Whatever! I feel like the more high-definition we can make that reality, it'll stop – it'll put an ease to – it'll slow down some of the incorrect assumptions that people make. And in our case unfortunately that can mean life or death.

ALI: No, I think it's not done often enough. And that's not to put any pressure upon any other artist. You talk about what you're feeling. But I think that's – it's really great that you do that.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: And I think all artists should have pressure. Be on that. Man, that's one thing I hate. And that goes back to what we were saying earlier too, when you put our work next to the work of them other people –

FRANNIE: I was just about to go –

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Yeah.

FRANNIE: That's the stakes.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Yeah, it's the stakes.

FRANNIE: When journalism fucks up, when the infrastructure isn't challenged, way way down the line, people die.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: And them artists ain't challenged either, and some of them that's marketed like they're the alternative don't be saying nothing, cause they don't have to, cause they're protected. They have infrastructure. They have investors. We out here doing this for survival. We have to say things. What I want from rap on that level, at least if you are in the position where you're supposed to be doing something different, I need everybody to be saying something.

ALI: Mhmm.

FRANNIE: Yep.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: I need everybody to be saying something, cause it is – it's life or death out here.

FRANNIE: Well, thank you for everything that you do.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Thank you. Thank you for everything that y'all do, man. This is great. So helpful. All this context and shit.

ALI: Word. Thank you.

OPEN MIKE EAGLE: Yeah. Thank you.